CHILDREN OF CIUDAD

ROMERO (EL SALVADOR)

By Rosa Jordan

Malibu

Surfside News, June

13, 1991

The

children of Ciudad

Romero have moved four times in the past six months. In November they

moved by boat and by foot from a refugee camp in the jungle to Panama

City. There they camped on the street outside the Salvadoran embassy

for two months, while their parents negotiated with the Salvadoran

government the right to return to their own country.

The

children of Ciudad

Romero have moved four times in the past six months. In November they

moved by boat and by foot from a refugee camp in the jungle to Panama

City. There they camped on the street outside the Salvadoran embassy

for two months, while their parents negotiated with the Salvadoran

government the right to return to their own country.

One of

the children who

made the move wrote to a child in Malibu, “The trip was very

difficult. We were four days with the bother of having nothing to

eat.”

At the

end of January the

Salvadoran government finally agreed to let the refugees return to El

Salvador, but only on condition that they settle in a

military-approved refugee camp.

The

teenagers, old enough

to remember life in El Salvador before the war had driven them out,

had hoped that they would be able to go back to their old home at La

Union. Or better yet, to a location on the coast where their parents

could form a fishing cooperative and they could enjoy El Salvador’s

beautiful black sand beaches.

Finding

themselves back in

El Salvador but on a high dry plateau of blazing sun and blowing dust

was not, to them, “coming home.” One boy named Alberto told me,

“I dreamed of coming back since I was five years old, but this

place with no trees, it was not what I dreamed. It was not my

country.”

The

adults must have felt

much the same, immediately realizing that there was no livelihood for

themselves or future for their children to be had here. It took them

ten weeks to find another place, but as soon as some abandoned land

was discovered, adequate for a camp of over 600 people, they took

their depressed teenagers and coughing babies, and without alerting

the military, quietly moved there.

Meanwhile,

the directors

of the community were working to obtain title to a 300-acre farm

where they could do more than camp; where they could stay, plant

crops, and build a town. The delegation from Malibu arrived as the

people of Ciudad Romero were in the process of this fourth—and they

hoped, final—move. We reached the farm at dusk, literally behind

the last truckload.

I was

awake most of the

night, lying in my tent or sitting outside in the starlight,

marveling at the calm. There were, I knew, over 300 children in this

camp. Not until near dawn did I hear one cry. Like their parents,

they were tired, and glad to be here.

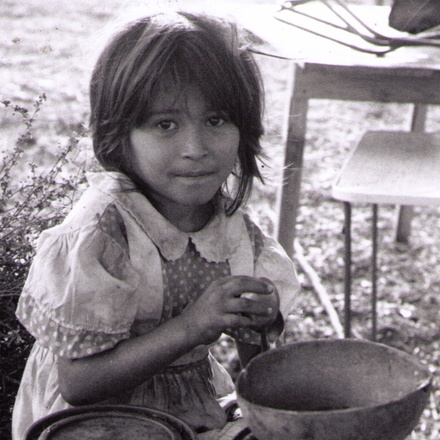

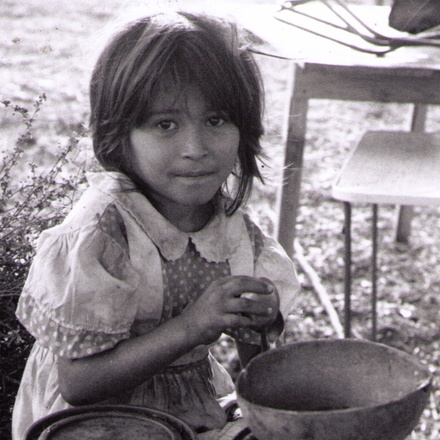

By

sunrise they were up,

and children as young as six were on their way to the river for

water. And there were other chores: collecting sticks from the

surrounding bush to keep cooking fires going, grinding corn for

tortillas, looking after younger siblings, carrying laundry to the

river to be washed.

Scores

of Malibu children

had sent letters and gifts to the children of Ciudad Romero. We had

planned to distribute them at school, but children who have moved

four times in the past six months, most recently the day before, do

not attend school.

We

sought out the

community’s youth director and explained about the letters and

gifts. He passed the word around, and on Saturday morning about 50

children came, dressed as if for school, and sat on hard wooden

benches under a canvas awning to receive their mail.

Among

the gifts sent from

Maliu children were school supplies: pens, pencils, crayons, paper.

When these had been distributed, the children laid their tablets in

their laps and wrote back.

Letters

from the children

of Ciudad Romero, like those they had received from students in

Malibu, were brief and decorated with drawings. The most common image

was that of a home, some sketching a picture of the tent they now

lived in, some drawing the house they would like to have. One boy

drew a simple outline of a house with no details except, on one side,

a large water faucet.

The

second favorite image

was that of a truck which the community had just purchased and which

is its only vehicle.

The

third most common

image to appear in the letters from the children of Ciudad Romero was

that of a helicopter. One child, whose page was filled with small

drawings, had labeled each thing: Mother. Dog. Duck. Tent. And

hovering above the mother, the dog, the duck, the tent, was a

helicopter which he had labeled: WAR.

Later

Malibu visitors

would see the frightened faces of children looking up at a

camouflage-painted Huey helicopter as it circled low over the camp,

guns protruding. But that day there were no helicopters over Ciudad

Romero.

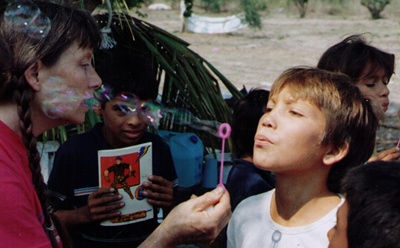

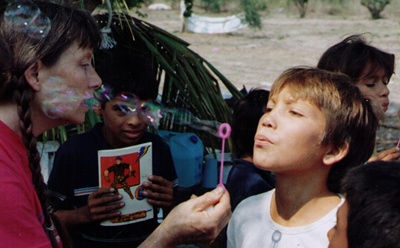

We

collected the

letters children had written to take back to Malibu, and distributed

gifts sent by the children from Malibu. We put pretty hair ties on

the girls’ ponytails, blew bubbles, and kicked the soccer balls

around. It was the happiest day of our visit. One thing more we might

have wished was that the children of Malibu could have been here,

too, enjoying this day of fun and peace that their sharing had

created.

The

children of Ciudad

Romero have moved four times in the past six months. In November they

moved by boat and by foot from a refugee camp in the jungle to Panama

City. There they camped on the street outside the Salvadoran embassy

for two months, while their parents negotiated with the Salvadoran

government the right to return to their own country.

The

children of Ciudad

Romero have moved four times in the past six months. In November they

moved by boat and by foot from a refugee camp in the jungle to Panama

City. There they camped on the street outside the Salvadoran embassy

for two months, while their parents negotiated with the Salvadoran

government the right to return to their own country.