Dangerous Places is the odyssey of a woman less concerned about personal safety than most of us because she believes that danger is an inherent part of life and contributes to our understanding of people, places, and politics. This fast-paced autobiographical adventure lures the reader into the fascinating, beautiful terrain of Mexico, Cuba, Guyana, El Salvador, Belize, Guatemala, Bolivia, Nicaragua, Peru, and Brazil. In those tracked and untracked places, the reader shares Jordan's search for those places where political and social realities intersect with personal courage and compassion.

***

Available from Café Books West, Rossland BC, from dot-com booksellers,

and from the author: Rosa Jordan $20, postage included.

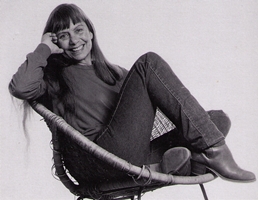

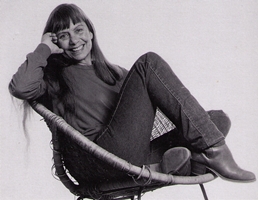

Photos by Larry Doell

Review from the Trail Times, May 21, 1997

Dangerous Places, the most recent book by Rossland writer Rosa Jordan, opens windows onto parts of the world most of us will never experience. Jordan's travels are unusual in that many of the places on her itinerary are ones we might have selected–a beach resort in Mexico, a ski area in Chile, or Mayan ruins in Guatemala–but for Jordan these are not destinations; they are jumping-off places.

A chapter that begins with an unproductive stay in an expatriate writers’ colony in Mexico evolves into a solo trek that is constantly changing directions, and ends with Jordan getting into a private plane of unknown destination with a man she has just met. More accurately, her trip begins there, a trip in which the real destination is one that most of us would prefer to avoid. That destination, which Jordan consciously seeks, is a place (or experience) located somewhere “beyond predictability.”

That unpredictable places can be dangerous is readily admitted. However, in several chapters each entitled “Leaving Home,” Jordan makes a convincing case that ones native land can be just as dangerous; that we only feel safer there because it is familiar. By contrast, unfamiliar places that seem terribly threatening are often the very ones that unfold into rare beauty.

The book is as unpredictable as Jordan’s travels. No chapter in Dangerous Places takes us where we think we are going. In the swing of a hammock, a stay at a tropical guest ranch turns heavily political. Picking up postcards in a shop leads to the illegal possession of an endangered wild animal. Being stuck overnight in an airport begins a chain of events that ends in a presidential palace. Even knowing that much does not tell the reader which experiences will turn out to be truly dangerous and which are happy adventures that we and she would love to relive.

For readers who revel in the unexpected, this book will be an adventure. Both the author and her travel destinations are revealed as something other than what we are likely to have know about that person and that place.

Interview by Ethan Baron

Though the book is composed of a multitude of vignettes, often dealing with Jordan’s experience of new places and people, her whole life is a trip, with the final destination as yet unknown. The development of her character and conscience, along with a couple of strong themes running through the book, serves to unify the story in a remarkable manner.

"I would not say that I am drawn to dangerous places, but life is a dangerous place. And it is there, in the shadow of love and violence, that I come face to face with courage,” she writes.

Jordan experiences the shadow of violence early on, watching white men beat black men in a Florida town. That event drives her onto the road for the first time, but she does not escape from violence. In fact, she gets closer to it, raped by a man with a gun, then threatened with death by a husband who puts a pistol to her head.

Such events give birth to a desire for flight, but once she starts travelling, her motivation changes. “Initially it was just to escape problems that were overwhelming me,” she says. “Very quickly it became a means of education, because at that time I had no formal education and I learned enormous amounts from travelling.”

Lessons in life come fast, and she soon sees that other people in the world are suffering at the hands of men with guns, resulting in traumas much more serious than her own. “The abuses I suffered were trivial compared to the abuses they suffered. It’s not even in the same league,” she says. She sees young children who’ve been mutilated by US-backed Contras in Nicaragua, Salvadoran soldiers kidnap boys to make them fight against their own people, and listens to an Argentinean colonel making small talk about killing young student activists.

“Camus says there’s a divine order of terror like disease and earthquakes, and there’s a human order of terror–war, torture, child abuse. And we can’t hope to win against either of them, but trying is what gives us our humanity, trying to fight against these things,” she says. “I do believe that in a way our humanity is strengthened by struggling against these orders of terror.”

Jordan’s ability to see the flip side of horror gives balance to her book. For every act of terror is an act of heroism or beauty. After talking to a gardener who has planted roses in memory of his wife, daughter and six Jesuits who were murdered by Salvadoran soldiers, Jordan writes, “It occurs to me that I have never been anyplace where so many individual faces appear so wholly good or evil. It’s as if the great neutral masses have been driven out, or changed. What remains are faces so cruel that no humanity is visible in them, and others of such profound goodness that they seem to exist on another plane.

Working as a journalist for travel publications and traveling for her own education, Jordan witnesses injustices rarely exposed in the mainstream media. “Conflicts tend to be described as government versus guerillas, so you have this view of armed forces against each other,” she says. “What I saw was armed forces, predominately government military and para-military, against unarmed people, and at that point political labels become irrelevant. If you’ve got any kind of humanity you take the side of the unarmed people.”

For her, merely taking sides isn’t enough. She lives by the credo, “All it takes for evil to succeed is for good people to do nothing.” She now works for Earthways Foundation, a California-based non-profit that funds projects in the less-developed world. “We have just completed a women’s chicken cooperative in northern Ecuador, and we’re in the process of starting a food self-sufficiency project in a Mayan village in northern Guatemala.”

Perhaps closest to her heart (and near to her conscience) is a project to set up a jungle cat sanctuary in Ecuador, an endeavor rooted in her strong emotional attachment to a margay (a small spotted wildcat she once kept. “I brought a baby margay out of the jungle, bought it from a hunter because its mother had been killed and he was raising it for its pelt,” she says. “A year later it escaped from my house and was killed by a car. What I got from that, and it’s been enshrined every since, is that there are no safe places for wild animals.” The margay Hopichen is closely tied to Jordan’s relationship with her daughter Jo, and the development of both relationships–even after Hopi is dead and Jo living on her own–serves to unify the stories of the book into a cohesive whole.

It’s an amazing feat, really bringing such a diversity of life experiences together. Jordan’s keen eyes, sharp ears, compassion and intelligence capture and relate a world (or at least a hemisphere) that few North Americans experience, and her colourful, clear imagery and easy narrative flow make Dangerous Places a pleasure to read from start to end.