Somewhere

if stopped

Somewhere

if stoppedLight into planes fuses

The collected motion of

Atoms stilled

Over its own transformation

Light.

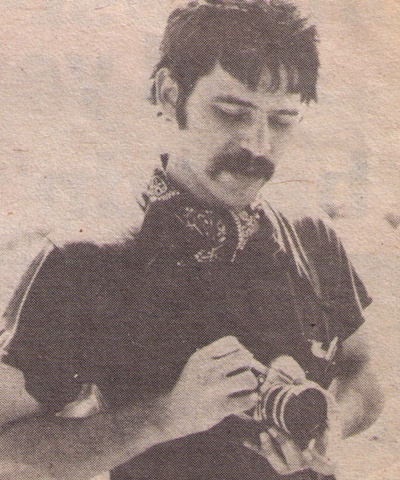

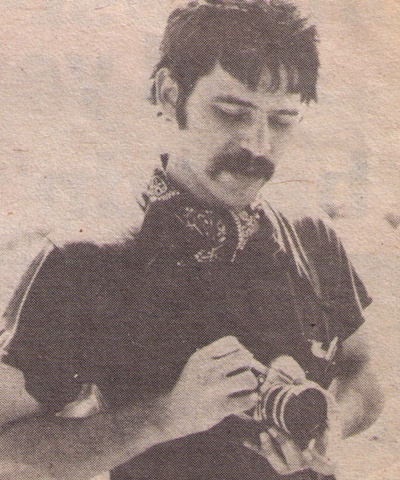

EPITAPH FOR A “LIGHT PAINTER”

By Rosa Jordan

Omaha Sun, December 16, 1981

He

couldn’t bear

photojournalism; photographic images, he felt, could be, should be,

art. Whether or not a universal truth, it was true of the work of

Omaha artist Don Swartz.

Don

Swartz is 34 now, but

the artist is dead; died four years ago, just before he turned 30.

Apart from his friends, not many noticed. There wasn’t a funeral or

anything like that.

It doesn’t seem that Don mourns his passing now, but he did, I believe, when he saw it coming. He was working on a book during that last year. Stuck in between the last completed pages of imagery and final blank ones, beginning neatly and ending in a scrawl, is this message:

“I am at the expiration of my totems. It is difficult now to afford the luxury of creativity. Something is missing…where the light is. I’ve lost the magic of the silver. Please advise.”

What did he mean, the light was missing, and that he had lost the magic of the silver? What was one to advise a person whose daily business, whose Omaha up-bringing, was as typical of the Nebraska good life as anyone’s?

Back in the Fifties, Donnie was a kid living on a tree-lined street with father, mother, and older brother. While the brother was playing ball and getting it together for his first car, ten-year-old Donnie charmed himself into a job with Photographers Associated.

They hired him as a model, this cute kid with the melting brown eyes, but within weeks his eyes were behind a camera, then in the darkroom, developing his own prints.

By age 18 he had his own portrait studio and could have been considered successful, except the temper of the times, as well as his temperament, insisted that success must be measured artistically as well as financially.

Instead of pursuing commercial portraiture, he photographed Woodstock, ghetto children, peace demonstrations, and Nebraska, city and country. He collaged photographic images of flowers, birds, a beautiful woman, and graveyard crosses into an anti-war poster, and on it he wrote, “If it is within man’s nature to fight, then let us all make war upon our will to kill.”

The first major exhibit of his work, when he was 23, was at the Sheldon Gallery in Lincoln. “Light paintings,” he called them, and wrote,

Somewhere

if stopped

Somewhere

if stopped

Light into planes fuses

The collected motion of

Atoms stilled

Over its own

transformation

Light.

His style evolved from expressive realism to impressionism to abstract compositions. But viewers who accepted abstraction in painting were not necessarily willing to extend it to photography. “What’s it supposed to be?” they insisted, and receiving no simple explanation from Don, didn’t purchase “light paintings” to hang on their walls.

In 1970, Don’s work was part of the Joslyn Museum’s Midwestern Biennial Art Exhibit. He built a dome in the lobby of the museum. One passed through the dome, with its continuous slide show of color imagery, en route to the rest of the exhibit. It was reviewed nationally, and afterwards he received generous offers to work for Kodak, 3-M Corporation, and television. He chose to stay in Omaha with his own work, not yet convinced that as an artist he could only rank among the starving.

He leased an old building in the Old Market and converted it into a massive studio, plus (in defiance of city code) an apartment on one floor. Antique lace curtains and hanging plants filtered sunshine into an immense room of brick and hardwood and art deco. The rent was next to nothing. Most months he could barely pay it.

He developed a process for printing photos on any surface—stone, glass, metal, wood—and in any size. The process was salable, if his own images weren’t. He did enormous wall-sized murals of old Omaha (taken from antique glass negatives) on several floors of the First National Bank. He splashed big murals on the walls of Hinky Dinky, Bozel & Jacobs ad agency, Gizmo’s Pinball Arcade, the College of St. Mary, Regency Plaza, and Liberty Square. He printed life-sized photographs of kids on paper-doll cutouts for Kidstuff Children’s Shop, and old-time flying machines in the parking structure at Eppley Airfield.

Through the Seventies, big jobs and money game together but something was falling apart. After a day’s work, friends noted that sometimes he was “high” or “out of it” for a day or two. Drinking? Drugs? Some, but no more (often less) than what they themselves were doing.

It was never certain what happened, but months later when Don’s brother returned to dismantle the studio he read labels on empty cans of polyurethane varnish that Don had used to spray-coat his murals: a list of toxic ingredients capable of causing damage to the central nervous system, and a warning not to use the product in vaporized form without a mask. Don had never used a mask.

Had he exposed himself repeatedly to neurotoxins, as one might smoke cigarettes or fail to use a seat belt, focusing on the job at hand and ignoring the laws of probability and his own vulnerability? It was a question that no one, least of all Don, ever could answer.

In January 19777, while in London to photograph an international pinball machine convention, Don’s brain ceased to make the connections necessary for memory, among other things. Demyelization—a breaking down of insulation about the nerves—had occurred. The phenomenon, although rare, is known in cerebral multiple sclerosis, in some genetic disorders, and, increasingly, in work situations where there is prolonged exposure to certain chemicals. Neurologists across the nation examined Don and considered different possibilities, but none really could say “what happened.”

There were occasional brief improvements; for a few months Don even remembered how to handle a camera. But now, at age 34, a ward of Douglas County Hospital, he doesn’t recognize his own photography. Friends rarely visit, for if they do, he doesn’t know them.

Do they know him, this strange stumbling man, speaking a gibberish of echoes, wearing the smile and cowboy hat of an artist they once admired? And how do you grieve for a person who dies, but doesn’t? Privately? Guiltily?

In the past Don had often spoken of leaving Omaha, but his roots went deeper than any desire for change. One of his last poems, titled “Omaha,” was an expression of that resistance and belonging to his home town:

Populated,

no pulse

Centerbalanced between

Corn growers, cow

butchers

And city servicing

scouts

Sucking up dirt that

runs

From the river;

Insurance orifice

Its name known,

Isolated faces,

transitory

Being born and dying

Like any other space

Was a man trying.

Died 1970. (consumed

gallons

Of alcohol). Bowling

average 275.

Giving me only a desk

calendar

Every year, and a

beginning

Into the light.

The light was fading. Don knew it. All he could do was keep his finger on the shutter, pen to paper, recording the artist’s view as long as there was light to work by.

Don Swartz, Omaha’s light painter, is four years gone now, into a body without coordination, a voice without coherence, a mind without artistic vision. But for 19 years he held a camera. With it he bequeathed to this city something of what his imagination captured from it. We retain the light he has lost.